- Home

- Celia Lottridge

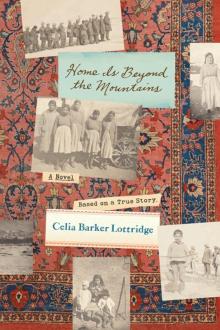

Home Is Beyond the Mountains

Home Is Beyond the Mountains Read online

Copyright © 2010 by Celia Barker Lottridge

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Distribution of this electronic edition via the Internet or any other means without the permission of the publisher is illegal. Please do not participate in electronic piracy of copyrighted material; purchase only authorized electronic editions. We appreciate your support of the author’s rights.

This edition published in 2011 by

Groundwood Books/House of Anansi Press Inc.

110 Spadina Avenue, Suite 801

Toronto, ON, M5V 2K4

Tel. 416-363-4343

Fax 416-363-1017

www.groundwood.com

This book was written with the support of an Ontario Arts Council Works in Progress Grant.

LIBRARY AND ARCHIVES CANADA CATALOGUING IN PUBLICATION

Lottridge, Celia B. (Celia Barker)

Home is beyond the mountains / Celia Barker Lottridge.

eISBN 978-1-55498-190-8>

I. Title.

PS8573.O855H65 2010 jC813’.54 C2009-906085-X

Cover photos of Hamadan Orphanage courtesy of Jane Montgomery

Maps drawn by Leon Grek

Design by Michael Solomon

We acknowledge for their financial support of our publishing program the Canada Council for the Arts, the Ontario Arts Council, and the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund.

For

Louise Shedd Barker

and

Marion Seary

who inspired me with their stories and

encouraged me with their listening

ONE

No Safe Place

Ayna, Persia

July 1918

A SOUND, A VERY quiet sound, woke Samira.

What was it? She listened but she kept her eyes tightly closed, hoping she could drift back into sleep.

“We always hear noises when we sleep on the roof,” she told herself. “It must be the donkey stamping its hoof, or Papa snoring.” She put out her hand and touched her little sister, Maryam, who was sleeping beside her. Maybe it was just a dream.

Then she heard it again. Metal clinking against metal and then a voice, whispering.

Samira sat up. The sky was clear and black. There was no moon, but the stars gave enough light that she could see Mama lying on her sleeping mat on the other side of Maryam. Beyond her was Papa and then her brother, Benyamin. They were all sleeping quietly.

She listened, holding her breath. Where had the sound come from?

There was no more clinking but the whispering came again.

Samira pushed her thin summer quilt aside and stood up. The clay floor was rough under her bare feet as she silently crossed the flat roof.

She was sure now. The whispering was coming from the garden behind the house. Boys from a nearby village sometimes sneaked into Ayna to steal a few ripe melons. Well, she would catch them this time.

There was a wall around the edge of the roof, but by standing on tiptoe Samira could see over it and over the wall that surrounded the village. The garden was on a hillside so she could see the almond tree and the rows of peppers and eggplants and the tangle of melon vines. Among the melons were three figures dressed in bulky clothes and wearing strange peaked caps.

No village boy wore such a cap, and these were not boys. They were men.

Then Samira saw a glint of starlight on something shiny. There it was again.

It was the blade of a knife. The man was lifting a melon and cutting it from the vine. He lowered it to the ground and its pale round shape disappeared.

“They are thieves,” thought Samira. “That man is cutting melons and putting them in a sack.”

The man stood up and lifted the sack to his shoulder, and Samira saw that he had a rifle strapped to his back. The knife in his hand clinked against the rifle barrel. That was the sound that had wakened her.

Samira turned to call for Papa but suddenly a hand gripped her around the ankle. She looked down and saw her father crouched beside her. He let go of her ankle and pulled her down and put his hand over her mouth.

He leaned close and whispered so softly that she could hardly hear him. “Be quiet. They must not know you saw them.”

Samira tried to open her mouth to ask a question, but Papa held his hand firm and whispered again, “I’ll tell you in the morning. Don’t stand up.”

She nodded and he let her go. She crawled over to her sleeping mat. Papa pulled the quilt up around her and patted her on the shoulder.

“Sleep,” he said without making a sound. Then he moved away on his hands and knees.

Samira reached for Maryam and pulled her close. For a long time she lay with her eyes open, listening. But it was quiet now, and after a while she fell asleep.

When she woke, she was alone. She sat up and looked around the roof that covered her house and the connected house where Uncle Avram lived with his family. On warm nights both families liked to sleep on the roof, out in the fresh air.

But now the sun was high in the sky. Everyone else would have drunk their tea and eaten their morning bread and cheese. Benyamin had probably gone to school, and Papa would be out in the garden.

Suddenly Samira remembered the dark figures stealing melons. She scrambled up, pulled on her skirt and blouse and climbed quickly down the ladder.

In the house it was bread-baking day. Mama was kneading dough in a big bowl while Maryam played with her doll as she always did while Mama worked.

But this morning Papa was there, too. He had a basket in his arms. It was empty except for one pale green melon.

“Samira,” he said. “I let you sleep because you were disturbed by the men in the garden last night. Do you remember anything about them?”

Samira closed her eyes, trying to see again the figures in the starlight.

“There were three of them,” she said. “They wore stiff jackets and caps that covered their ears. They had knives and they were cutting melons.” She opened her eyes. “And they had rifles. Who were they, Papa?”

“Uniforms and guns,” said Papa. “They were soldiers, not ordinary thieves. I’ve heard that deserters from the Turkish army have come through the mountains into Persia. They don’t want to fight in the war anymore but they don’t mind stealing. They were hungry and our melons are just getting ripe. This is the only one they missed.”

“What if they come again?” said Samira.

“We must stay quiet and be watchful. I told Benyamin to come straight home after school. No one should be wandering around the countryside. I’m going out to the garden to pick whatever is ripe or nearly ripe. If the soldiers do come back they won’t find much to steal.”

He handed the melon to Samira and left.

Mama set the bowl of bread dough to one side and said, “Get some bread and cheese for your breakfast and take Maryam next door to play with Ester and

Negris. Sahra will come soon to bake bread with me, so I’m going to uncover the oven now and build up the fire.”

The oven was a round hole dug into the earthen floor of the house, lined with smooth clay and covered with a lid. The fire burned at the bottom and most days an iron pot filled with the day’s stew was set to cook down inside the oven with the top almost closed. But on bread-baking day the cover was left off. It would be too easy for Maryam to stumble and fall in.

Aunt Sahra and Mama would pat the bread dough into big thin ovals. Mama would slap the ovals onto the hot sides of the oven. In just a few minutes the bread would be brown and bubbling. Aunt Sahra would lift it off with wooden tongs. By the end of the baking there would be a pile of lawash flatbread, enough to last both families for a week or more.

Samira took Maryam out onto the terrace. There was an oven out there, too, and in the summer Mama and Aunt Sahra always baked bread outside. But today things were different.

Maryam tugged at her hand and the two girls walked to the next wooden door and into a house that was almost exactly like theirs. There was just one room, square with whitewashed walls. The only furniture was a big carved chest where sleeping mats and quilts and clothes were stored. The floor was covered with beautiful rugs and there were cushions to sit on, though the children usually sat on the floor.

Aunt Sahra was busy tidying up. As always she moved quickly and talked even faster.

“I want you girls to play in the house today,” she said. “There are too many strangers around.” So Samira knew that she had heard about the soldiers in the garden.

When all the breakfast crumbs had been brushed away and the tea glasses washed, she looked at the four girls.

“Ester and Samira, I want you to take good care of your little sisters,” she said. “If anything strange happens, call me at once.”

She didn’t pick up her basket and leave until Ester nodded and Samira said, “Yes, Aunt Sahra.”

Samira wondered what her aunt was thinking. Bread-baking day was always the same. But it would be easy to let Aunt Sahra and Mama know if anything did happen. There was a hole in the wall between the two houses. It was just above Samira’s head and big enough for her hand to fit through. Most of the time the hole was blocked by a roll of cloth, but the cloth could be removed. Then people on either side of the wall could talk to each other.

The hole was open now. They were not really alone.

“Let’s play school,” said Ester. She was seven, just two years younger than Samira. Like Samira she longed to go to school, but so far no teacher for the girls had come to the village. The Assyrian Orthodox Church ran the boys’ school, and the priest had promised that one day the girls would have a school, too.

Samira and Ester thought they would probably be grown up before this happened.

Sometimes they peeked into the schoolroom next to the church, so they knew that the teacher should have a chair and a table and big board to write on. The pupils should have little boards and chalk so that they could copy what the teacher wrote. And there should be a book for the teacher and some pages with writing on them so that the pupils could practice reading.

All of this was easy to pretend. Samira was the oldest so she was the teacher. She sat on the fattest cushion. Ester and Negris, who was five, were good pupils. They sat quietly on the rug and listened to the teacher and practiced writing with their fingers on flat pieces of wood. Maryam was only three and she was not a very good pupil, though sometimes she would sit with her doll and listen to a story. Today she wanted to sit very close to Negris. Maybe she had heard something in the night, too.

Samira stood up and turned to the wall behind her cushion.

“Today I have something special to teach you,” she said. “Last Sunday when we were waiting for Mama and Papa to come home from the church, Benyamin taught me the first three letters of the Syriac alphabet. He promised to teach me more, but this is the beginning.”

She pointed at the wall.

“This is the board where I will write the letters. Watch closely. This is alap, the first letter.” With her finger she made a straight bottom line with a dot above it and a curved line that connected the dot to the line.

Of course, her finger made no mark on the wall, but she hoped the little girls would get the idea. She drew the letter again and then stopped.

Through the hole in the wall she heard Aunt Sahra’s voice clearly. It was high and fierce.

“Even if you do go, I’m staying here. Or I’ll go to the city with the girls. But army or no army I’m not going far until Avram comes home.”

Avram was Sahra’s husband. He had set off on a long journey to the city of Tabriz across Lake Urmieh to inquire about taking his whole family to America. He said Persia wasn’t safe anymore.

Samira suddenly realized that the other girls were staring at her, waiting for her to draw another letter. Sitting on the floor, they hadn’t heard Aunt Sahra’s voice. And now Samira couldn’t hear it, either. Her mother must have reminded Aunt Sahra that walls have ears. Now there was no sound of voices, only the slap of the bread against the wall of the oven.

“You’re the teacher, Samira,” Maryam said. “You have to talk.”

Samira blinked.

“Yes,” she said. “I was just thinking about the second letter. It’s beet and it looks like this.”

When the bread was all baked, Aunt Sahra came back. She set down her basket filled with a stack of lawash and tidied up the cushions the girls had used, just as she always did. But she was so quiet that all four girls became quiet, too.

Samira wanted to ask Aunt Sahra what she meant when she said, “Army or no army.” But she didn’t.

Suddenly her aunt noticed that her nieces were still there.

“My goodness,” she said. “You and Maryam should go home now, Samira. There is work to be done and your mother needs your help.”

Then she remembered to hug them quickly before she opened the door and gave them a little push toward home.

AT HOME THE FLOOR was covered with baskets of eggplants and squash and peppers. Papa had done just what he’d said he would do. He had picked everything in the garden.

Mama was standing among the baskets shaking her head.

“We have to cut up all these vegetables so we can spread them to dry tomorrow,” she said.

“The squash are so small,” said Samira.

“I know. It’s too soon to pick any of this. But we have to keep it safe or we won’t have enough to eat in the winter. Now go and get a knife so we can get started.”

Samira nodded and went to get a small knife from the shelf. She had questions but she knew this was not the time to ask them.

By suppertime the baskets were filled with neatly sliced vegetables, and the stew that had been cooking in the oven was ready to eat. The family sat in a circle around the big clay bowl and took turns scooping up the savory stew with torn pieces of fresh lawash.

They were all quiet. In summer they usually ate on the terrace, and the children finished quickly so they could play with their friends before darkness sent everyone to bed. Tonight no one wanted to move even when the bowl was empty.

At last Benyamin spoke. “We didn’t have lessons today at school. Instead our teacher told us that we must remember that we ar

e Assyrians and we have been here in Persia for centuries. All through history we have had our villages and our orthodox churches and our own language, Syriac. No matter what happens we must remember that we belong here.”

Papa said, “Your teacher is right. But the Turkish army doesn’t care that this is our home. They are fighting in a big war with many countries and they are using the war as an excuse to cross into Persia to take our land. The British army might want to protect us but it is far away to the south. Persia is not in the war and it has no army so there is nothing to stop these soldiers from driving us from our villages. From what I hear, the soldiers are in the mountains now, attacking the villages there. We may be safer because we are near the city of Urmieh. There are people in the city from America and from France who want to protect us. Maybe they can help. We have to watch and wait.”

When it grew dark Papa said it was not safe to sleep on the roof, so the family spent a stuffy night in the house. They all woke up very early.

As soon as they had eaten, Mama sent Samira to lay clean cloths on the roof. Together they would spread the cut vegetables to dry. Later they would store them in the umbar, the cellar under the terrace, to be used for soups and stews all winter.

When she got to the roof, Samira took a minute to watch Benyamin and the other village boys run down the street on their way to school.

She was just turning away when she heard the sound of galloping horses. She listened.

People in the village did not have horses. Their donkeys and mules walked slowly, carrying heavy loads. Galloping horses meant strangers.

In no time at all, the narrow road outside the village wall was filled with men on horseback. They wore turbans and had cartridge belts slung across their chests and sabers stuck in their belts. Samira knew they were Kurds — mountain people who often came through the village selling rugs and sometimes raiding the orchards and flocks. People told many stories about the Kurds — how they would stop travelers and take all their money and belongings or, sometimes, show them a better way through the mountains.

Home Is Beyond the Mountains

Home Is Beyond the Mountains